(There’s also an English translation of this text below the image in this post.)

Vi minns inte alla timmar

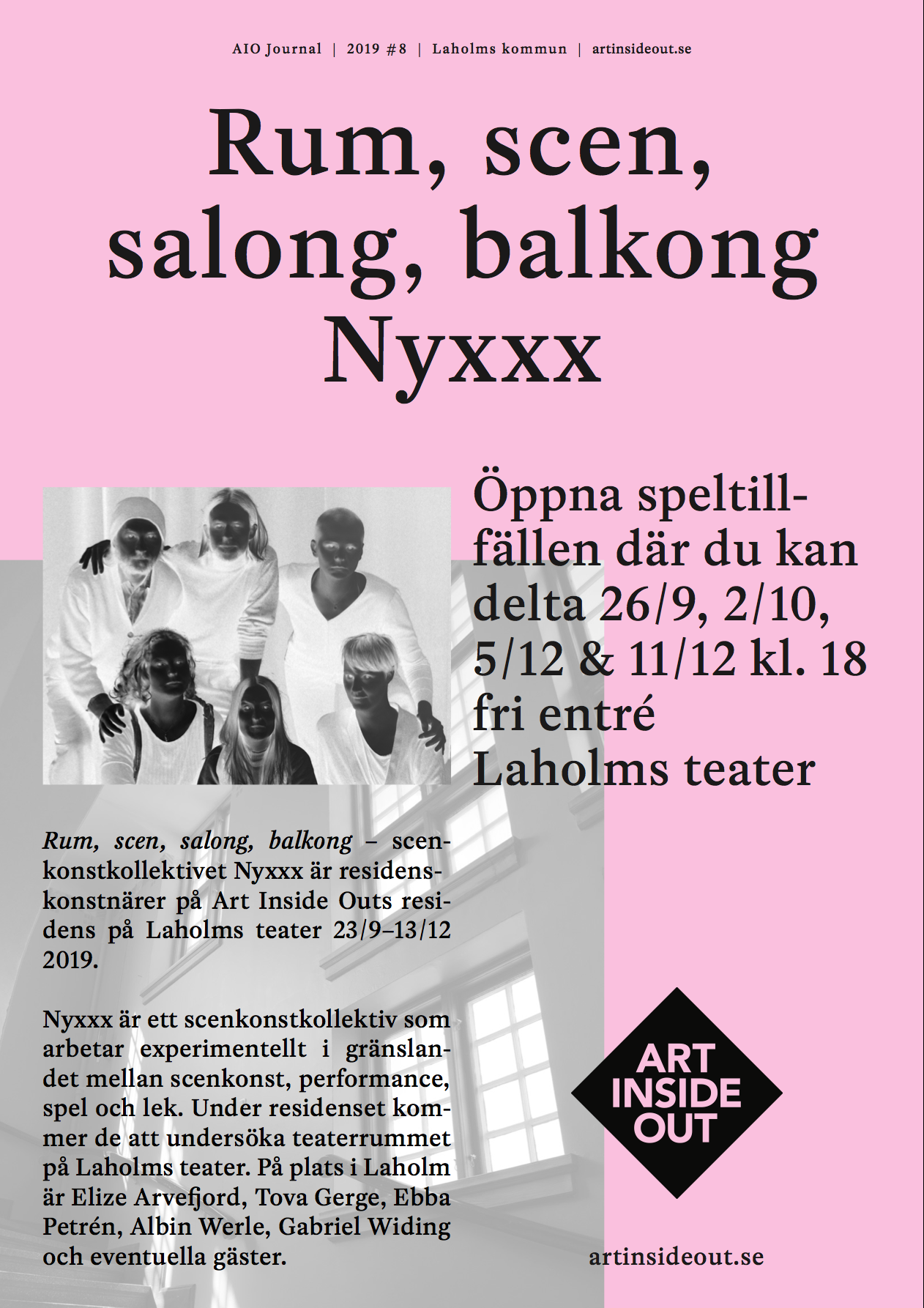

Tova Gerge: Ebba Petrén och Gabriel Widing från scenkonstkollektivet Nyxxx är kanske mina mest återkommande reskamrater, och våra resandepraktiker är ofta ömsesidigt beroende även när vi inte reser tillsammans. Jag bjöd in dem i samband med mitt projekt Working on Travel aka Trains and Boats and Planes för att prata om våra gemenskaper och skillnader i resandets begär och politik. De berättade mycket, och ställde en del frågor tillbaka. Det samtalet resulterade i den här texten, och en podcast som finns att lyssna på här.

Tova Gerge, Ebba Petrén & Gabriel Widing:

Gabriel: Jag har länge tänkt på mig själv som en liten kropp som plockas upp av en stor fågel och sedan kastas ner någonstans där det behövs. Fågeln är förstås kapitalet. Fågeln kan försätta mig i minst tre olika sorters resande. Jag kan hamna i Porto Alegre eller Tokyo, platser som jag kanske aldrig återvänder till. Jag kan hamna på flyg till städer i Europa där man talar andra språk. Eller, och det är det vanligaste för mig, så hamnar jag på tåg och bussar genom Sverige till olika funktionalistiska lägenheter. Den sortens resor är trygga för mig. Alla tåg är likadana, alla små svenska städer är likadana, alla gästlägenheter är likadana, alltid samma affischer från åttiotalet på väggarna.

Ebba: Jag känner mig inte fullt så lealös. Jag menar att det kan finnas båda en vilja och en ovilja att resa som saknas i den fågelbilden. Därmed inte sagt att den viljan är oberoende av vad som händer oss. En kompis sa: ”Det är så himla skönt att inte ha fast anställning! Jag vill prova på många saker så här i början av mitt yrkesliv!” och sen efter sex månader fick hen fast anställning och sa ”Det är så bra att ha en fast anställning! Jag kan alltid ta tjänstledigt, men det är också bra att vara på ett och samma ställe så att jag kan få kontinuitet såhär i början av mitt arbetsliv!”

Gabriel: Det finns väl en del kontinuiteter även i vårt arbetsrelaterade resande. Redan för tio år sedan reste vi mycket mellan Stockholm och Malmö där vi arbetade med verk för olika teaterinstitutioner. Sedan har vi gradvis utvidgat det territoriet, så att vi arbetar på ett liknande sätt i andra svenska städer.

Ebba: Vi har pratat om det som att vårt geografiskt utspridda kollektiv – just nu sex personer i fyra städer – kan täcka en större värld. Men jag tror också att sättet vi reser på påverkar hur vi gör konst. Vi stoppar det vi upplever på scen. Och då tänker jag främst på resor som sätter djupare intryck. Vi minns inte alla timmar på olika SJ-tåg, vem vi satt bredvid. Däremot kanske vi minns tågresan vi gjorde i Japan till Hakone och berget Fuji.

Gabriel: Ja, vårt besök i Japan inverkade på vår estetik i ett par år.

Tova: Märks det också när vi har varit i funktionalistiska lägenheter i hela Sverige?

Gabriel: Det lägger väl en sorts fadd, socialdepressiv filt över allt? Man märker det kanske till exempel i en radioföljetong som vi skrev där huvudkaraktären reser runt med en mystisk inspelningsapparat i hela Sverige och pratar med spöken.

Tova: Jag vill inte resa runt längre. Jag vägrar mer och mer att resa långt om jag kan undvika det. Visst, jämfört med en vanlig yrkesarbetande person i Stockholm reser jag mycket. Men om jag förut var borta halva året så är jag numera borta kanske två månader på ett år.

Gabriel: Jag tror att jag har varit borta 25-30 veckor per år i typ fem år.

Tova: Jag tänker på att när man är organiserad av arbete så är det arbetet man ser. Man kommer till en plats och vistas i en studio och lära känna den institutionen och vet hur producenten ser ut och går till H&M på huvudgatan, men man har ingen aning om vad som försiggår i övrigt, för att när man går från jobbet är man alldeles för trött för att ta några sociala initiativ.

Ebba: Jag har tänkt på de sociala relationerna i det där med att hela tiden ha nya kollegor. Man är väldigt sårbar på ett sätt. Man har ingen att prata med när man kommer hem från jobbet. Om jag jobbar som regissör är det många dagar där de enda konversationerna jag har är med människor som ser mig som den där regissören. I början får man alltid känna att man är intressant för att man är ny, men förälskelsefasen går över, och då visar det sig ibland att vi inte hade samma bild av projektet. Då kan det bli väldigt obekvämt, för det finns ingen intimitet eller tillit att falla tillbaka på i de relationerna. Och om tilliten återupprättas efter premiären – ja, då är det i vilket fall dags att åka hem.

Tova: Jag tänker på Tinder och konsumtionsdejtande som någon sorts parallell till det där med institutioner som söker en konstnärsförälskelse: och så tar det slut, och så bara gör man om det med en ny. Den parallellen är intressant för mig därför att jag vet att ni har använt den typen av sociala medier för att försöka skapa relationer på platsen ni kommer till.

Gabriel: Det man begär är inte nödvändigtvis intimitet eller sex. Det kan vara att få prata med någon som är förankrad i en plats, som har ett liv i den där lilla staden. För det händer inte spontant.

Ebba: Jag kommer ihåg när vi var i Borås Gabriel, och både du och jag var ute på Tinder. Jag kom hem och sa: ”Det finns ett område där folk har musikstudios och svartklubbar!” och du sa: ”Det finns folk som gör mode och design på en skola!” Vi var bara fett glada att det fanns folk. Men det är ju klart det gör!

Gabriel: Man vill veta att det finns ett liv. Det kan finnas olika strategier för att få kontakt med det. Dejtande är en strategi. En annan är att leta efter det som är likadant var man än är. Som att Coca-Cola alltid smakar likadant, och då hugger man tag i den. Eller så kan man förkovra sig i det ortsspecifika: man går på länsmuseet i Jönköping eller arbetets museum i Norrköping eller läser om Huskvarnas vapenindustri på sjuttonhundratalet…

Ebba: Den där sista strategin känns också som att den legitimerar att jag ska få verka på en plats. Jag känner nästan avsmak för mig själv när jag kommer till ett ställe och ska föreslå någonting med den där förälskelseinställningen utan att ha någon aning om vad de har gjort där tidigare, vad de har gått igenom som ort. Vilka är vi om vi inte vet det? Är vi de som ska komma och befria dem från deras historia?

Tova: Jag tänker på hur vi pratar om urbanitet och landsbygd i det här samtalet. Vi bor i stora städer, och arbetar i små städer. Det är ganska vanligt att det ser ut så inom vårt konstfält. Jag undrar om det kan förstärka någon typ av landsbygdsförakt när jag bara blir utslängd till olika orter där jag inte nödvändigtvis vill vara, där jag inte har något nätverk, där jag hela tiden längtar efter någon annan, någon annanstans. Då börjar man lätt karikera den där orten.

Ebba: Samtidigt startades länsteatrarna ofta av folk som oss – en grupp från Stockholm eller Teaterhögskolan i Malmö – fast på sjuttiotalet, som flyttade till Sundsvall eller så och började få pengar. Det kanske sker på andra sätt också nu. Som att Institutet har flyttat till Tornedalen och startat en scen i byn som en av medlemmarna kommer ifrån.

Gabriel: De mest negativa upplevelserna av att vara på resa är ju när man inte fattar vad man gör där, hur man hamnade där.

Ebba: Jag tycker om att åka till en plats och bli väl mottagen som expert på någonting. Att få säga sin mening, kanske kunna ta i lite extra eftersom man ändå inte riktigt har något ansvar och sedan åka hem. Det svåra är när jag ska ha en vardag fast alla saker som är vardag för mig saknas. Vi har ganska olika strategier kring de perioderna, Gabriel. Jag pratar länge och mycket i telefon med nära vänner eller partner. Jag behöver deras stöd. Och innan en sådan period blir det extra viktigt att det ska vara tryggt.

Gabriel: Jag är mer så att jag checkar ut. Jag säger: ”Vi ses om åtta veckor.” Det funkar bra för mig, men det funkar inte bra för dem jag lämnar hemma.

Ebba: Det händer mig ofta att ingen vet var jag är. Jag kan träffa folk i Stockholm som säger ”Bor du i Malmö?” Och det hänger på mig att ta kontakt. Jag är inte med i folks vardag, för jag har varit borta och sagt nej så många gånger. Och jag kan känna det som att jag är på fel plats när jag är på alla de där andra platserna. Det kan handla om vilka jag känner mig nära: hur människor ser ut, hur deras affischer ser ut, hur de pratar om konst. De gånger jag inte känner någon attraktion till det som finns omkring, men ändå måste spegla mig i det, upplever jag min egen konst som futtig. Kanske är det fåfänga; att jag vill gå på rätt fest. Samtidigt måste jag kunna ta på allvar att jag och vi i Nyxxx kan utvecklas mer och förstås på ett annat sätt i andra sammanhang. För jag har också varit i sammanhang där det har känts helt rätt.

Gabriel: Jag hade gärna rest mer till stora städer om jag hade fått välja, som Prag eller Krakow snarare än andra platser mellan Stockholm och Malmö. Men de flesta som turnerar internationellt verkar få spela sina föreställningar så få gånger jämfört med oss som främst rör oss i de svenska regionala nätverken.

Ebba: Jag känner mig ändå lite olycklig över var jag befinner mig ibland. Jag tror också det handlar om att alla i Nyxxx är mer och mer busy med sitt. ”Nu kan vi spåna lite idéer på messengertråden” – okej, men jag har inte pratat med Gabriel på ett halvår för vi har inte haft tid med det, och hur ska vi då kunna komma någonstans?

Gabriel: Det är svårt att ses spåna idéer utan att ha ett färdigt projekt med full finansiering. Det är som ett moment 22. En arbetsvecka med ett sexpersonerskollektiv kostar ju 70 000 kronor.

Ebba: Eller så måste man umgås på fritiden.

Tova: Men då kanske man är i Värnamo och hatar små orter. Eller är trött på att hela tiden hänga med sina kollegor och vill ha en relation med sina kompisar. Jag räknar er som mina kompisar, men det kan vara svårt att hitta till den platsen när vi har jobbat mycket ihop.

Ebba: Jag tycker att många mindre orter har spännande historia.

Tova: Ebba, du har ju också på ett sätt flyttat till en småstad, du har ett hus på en ort som heter Ljusne. Upplever du att Ljusne har någon speciell roll i relation till de här berättelserna om arbete och rörlighet?

Ebba: Det är mycket som har förändrats i mindre städer, inte bara i Sverige utan i hela Europa, som har att göra med kapitalflykt och postindustriella tillstånd. Det visar tydligt hur möjligheterna och drömmarna i ett liv står i relation till pengar och arbete. Jag tänker också på vad som händer när det finns plats någonstans: vem som kommer för att ta den platsen, och vad det innebär för dem vars plats blir tagen. PAF till exempel ligger i en pittoresk fransk by med ett vackert landskap, men det är också ett mikrokosmos i sig, isolerat från bygden. De i byn har inte alltid älskat verksamheten på PAF, trots att det har gjorts försök att minska spänningarna.

Tova: Kan inte du berätta den där historien om Ljusne och sågverket?

Ebba: En gubbe cyklade upp på min infart häromdagen. Han letade efter en katt. Jag kom ut och sa hallå och berättade att jag var nyinflyttad. Han sa: ”Jag har bott här sedan 1964. Det var en annan plats då, jag är så förbannad över hur det har blivit. Det var 5000 personer som bodde här, det fanns 4000 arbetare på fabriken…” Så är det med varenda jävel du träffar i Ljusne. Porten till historien står öppen, och hatet till Hallwylska familjen är så djupt. Hallwyl gifte in sig i familjen som ägde fabriken. Det var en handelsfamilj som skeppade så kallade kolonialvaror till södra Norrland via hamnarna i Söderhamn och Ljusne. Sedan köpte de skog av bönderna, och sedan byggde de sågverket, och anställde bönderna så att bönderna kunde få pengar och köpa kaffe och sprit som de hade skeppat in i sin hamn. Och pengarna kanaliserades till Hallwylska palatset som byggdes utan övre gräns i budgeten. Det finns många orter som har varit med om det här, men det blir väldigt tydligt med Hallwylska palatset. Hon som byggde Hallwylska palatset hade som ambition att katalogisera allt redan från början. Min fantasi är att hon måste ha vetat att den exploatering som skedde av skogen och arbetarna i Ljusne med omnejd var helt ohållbar. Lika bra att göra ett museum direkt.

Gabriel: Man borde göra bussresor från Ljusne till Hallwylska.

Ebba: Det brukade fackklubben på plywoodfabriken göra. De stod och grät därinne när de såg alla guldkranar.

Tova: Kommer vi att stå och gråta någonstans, och i så fall var?

We can’t remember all the hours

Tova Gerge: Ebba Petrén and Gabriel Widing from the performing arts collective Nyxxx are perhaps my most frequent co-travellers, and our practices of travelling are often mutually dependent even when we are not travelling together. For my project Working on Travel aka Trains and Boats and Planes, I invited them both to talk about what we have in common and what separates us in the desires and politics of travelling. They told me a lot, and asked me some questions too.

This text is based on a conversation that also is available as a podcast in Swedish (see above).

Tova Gerge, Ebba Petrén & Gabriel Widing:

Gabriel: For a quite a while, I’ve been thinking of myself as small body occasionally picked up by a large bird and then thrown down somewhere where I’m needed. ”. The bird is the capital, of course. The bird can plunge me into at least three different kinds of travels. I might end up in Porto Alegre or Tokyo, places I might never return to again. I might end up in different cities in Europe where people speak other languages. Or, and that’s what’s most common for me, I end up going by train and bus through Sweden to various modernistic apartments. That type of travels is very safe for me. All the trains are the same, all small Swedish cities are the same, all guest apartments are the same, always the same posters from the eighties on the walls.

Ebba: I don’t feel quite that limp. Both desire and repulsion can appear in relation to travel, but the bird image doesn’t show that. However, I don’t mean that desire and repulsion are independent of what happens to us. A friend once said: “It’s so damn nice not having a steady job! I want to try out many things now right at the start of my career!” but six months later when this friend had got a steady job, ze said: “It’s so good to have a steady job! I can always take a break, but it’s also good being in one and the same place so I can get some continuity now right at the start of my career!”

Gabriel: Surely there is some continuity in our work travels as well. Already ten years ago we used to travel between Stockholm and Malmö, making pieces for different theatre institutions. Then we have gradually expanded that territory, working in similar ways in other Swedish cities.

Ebba: We have said to each other that our sprawling collective – six persons in four cities – can cover a larger world. But I also think that the way we are spread out is influencing the way we do art. We put our experiences on stage. And then I mostly think of travels that leave deeper impressions. We can’t remember all the hours on Swedish trains, who we sat next to. On the other hand, we might remember the train journey we did in Japan to Hakone and Mount Fuji.

Gabriel: Yes, after we went to Japan, that impacted on our aesthetics for a couple of years.

Tova: Can you also tell if we’ve stayed in modernist apartments all over Sweden?

Gabriel: I guess it puts a damp, social-depressive cloth on everything. Maybe you can tell for example from a radio series that we wrote where the main character travel around with a mystical recording device in all of Sweden, talking with ghosts.

Tova: I don’t want to travel around any longer. I more and more refuse to travel far if I can avoid it. Sure, compared to an ordinary person working in Stockholm I travel a lot. But whereas I was away half the year before, I’m now gone maybe two months a year.

Gabriel: I think I’ve been away 25-30 weeks per year for like five years.

Tova: I’m thinking: when you’re organised around work, that’s what you see. You come to a place and spend your time in a studio and get to know that institution and what the producer looks like, and you go to H&M on the main street, but you have no idea what is going on apart from that, because when you leave work, you’re way too tired to be sociable.

Ebba: I’ve thought about the social implications having new colleagues all the time. You’re very vulnerable, in a way. You have no one to talk to when you get home from work. If I work as a director, there are many days when the only conversations I have are with people who see me as that director. In the beginning, you always feel that you’re interesting because you’re new, but the infatuation fades, and then sometimes it turns out that we didn’t share the same project vision. Then it can get very uncomfortable, because there is no intimacy or trust to fall back on in these relationships. And if the trust is re-established after the premiere – well, then it’s time to go home.

Tova: I’m thinking of Tinder and binge-dating as a kind of parallel to that thing with institutions looking for artist infatuations: when it ends, you just do it again with someone new. That similarity is interesting to me, because I know you’ve used that type of social media attempting to create relationships in the places you go to.

Gabriel: What you’re after is not necessarily intimacy or sex. It can be getting to talk to someone who has roots in a place, who has their life in that little town. Because that doesn’t happen spontaneously.

Ebba: I remember when we were in Borås, Gabriel, and both you and me were on Tinder. I came home and said, “There’s a district where people have music studios and illegal clubs!” and you said, “There are people doing fashion and design in a school!” We were just so happy to find people. But of course, there are people!

Gabriel: You want to know there is a life. There might be different strategies for tapping into that. Dating is one strategy. Another is to look for the things that are the same wherever you are. Like: Coca-Cola always tastes the same, so then you latch on to that. Or you can cultivate your knowledge of the place specific: you visit the regional museum in Jönköping or the museum of work in Norrköping or you read up on the weapons industry in Huskvarna in the 16th century…

Ebba: That last strategy also feels like it legitimises that I’m active in a place. I almost feel disgust for myself when I come to a place and propose something with that infatuated attitude without having the slightest idea what they’ve done there before, what they’ve been through as a region. Who are we if we don’t know that? Are we the ones coming to save them from their history?

Tova: I’m thinking of how we talk of urbanity and countryside in this conversation. We live in big cities, and we work in small cities. It’s quite often like that in our artistic field. I wonder if that can enhance a kind of contempt for the countryside, being thrown out to different places where I don’t necessarily want to be, where I don’t have a network, where I constantly long for someone else, somewhere else. It makes it easy to fall into caricaturing that place.

Ebba: At the same time, many of the regional theatres were started by people like us, but in the seventies: a group from Stockholm or Malmö Theatre Academy that moved to Sundsvall or such and got startup money. Maybe this also happens now to a certain extent. Like the Malmö-based performance group The Institute moving to Tornedalen and starting a new venue in the village where one of the members grew up.

Gabriel: The most negative experience of being on tour is when you don’t get what you’re doing there, how you ended up there.

Ebba: I like to go to a place and be well received as an expert of something. To get to voice my opinion, maybe put some extra force into it since I don’t really have any responsibility, and then go home. They’re happy, no one knows my weak spots and I can just shine. The hard thing is when I’m supposed to have an everyday life even though all the things that are everyday life for me are missing. We have quite different strategies when it comes to these periods, Gabriel. I have long conversations on the phone with close friends or my partner. I need their support. And before such a period, it’s even more important that it’s safe.

Gabriel: I check out instead. I say, “See you in eight weeks.” That works for me, but it doesn’t work well for everyone I’m leaving back home.

Ebba: It often happens to me that no one knows where I am. I meet people in Stockholm who ask, “Do you live in Malmö?” And it’s up to me to stay in touch. I’m not part of people’s everyday life, because I’ve been away and said no so many times. And I can feel like I’m not in the right place when I’m in all these other places. It might be about who I feel close to: what people look like, what their posters look like, how they talk about art. The times I feel no attraction, but still have to mirror myself in it, I can experience my own art as being trivial. Maybe it’s vanity; that I can’t imagine that the party I’m invited to is the right one. At the same time, I need to be serious about me and all of Nyxxx developing and being understood differently in a different context. Because I’ve also been in contexts where I’ve felt everything is right.

Gabriel: I would have wanted to travel more to big cities if I got to choose, like Prague or Krakow rather than other places between Stockholm and Malmö. But most people touring get to play their performances so few times in comparison to us moving mostly in the regional Swedish networks.

Ebba: I still feel a bit unhappy about where I am sometimes. I think it’s also about everyone in Nyxxx being more and more busy with their own stuff. “Now let’s juggle some ideas on Messenger” – okay, but I haven’t talked to Gabriel for six months because we haven’t had time, so how are we supposed to get anywhere?

Gabriel: It’s hard to meet and juggle ideas without already having a set project with full funding. It’s like a catch 22. A working week for a six-person collective costs like 70,000 SEK.

Ebba: Or you have to hang out in your free time.

Tova: But then you might be in Värnamo, busy hating small towns. Or you’re tired of hanging out with your colleagues and want to be with your friends. I count you as my friends, but it can be hard to find the way to that space when you’ve worked so much together.

Ebba: I think many small towns have a fascinating history.

Tova: Ebba, you’ve also moved to a small town, in a way. You have a house in a town called Ljusne. Do you experience that Ljusne plays a specific role in these stories about work and mobility?

Ebba: A lot has changed in smaller towns, not just in Sweden but all over Europe, due to flight of capital and post-industrial conditions. It shows clearly how the possibilities and dreams in a life stand in relation to money and work. I’m also thinking of what happens when there is space somewhere. Who comes to occupy that space, what does it mean for those who have their space occupied? PAF (Performing Arts Forum), for instance, is in a picturesque French village with a beautiful landscape, but PAF is also a microcosm in itself, isolated from the rest of the area. People in the village haven’t always loved the activities at PAF, and there have been some attempts to reduce the tension.

Tova: Tell us that story of Ljusne and the sawmill!

Ebba: An old man biked up my driveway the other day. He was looking for his cat. I came out and said hi and told him I had just moved in. He said, “I’ve lived here since 1964. It was another place back then, I’m so pissed-off about what it has become. 5,000 people used to live here, there were 4,000 workers at the factory…” And it’s like that with every bugger you meet in Ljusne. The door to history flings open, and the hate for the Hallwyl family is so fierce. Hallwyl married into the family that owned the factory. It was a merchant family that shipped so-called colonial goods to southern Northland from the ports in Söderhamn and Ljusne. They bought forest land from the farmers and built the sawmill and hired the farmers so the farmers could get money and buy coffee and liquor that came into their port. And the money was siphoned off into the Hallwyl Palace that was built without an upper limit in the budget. There are many places that have experienced this, but Hallwyl Palace is such a distinct example. The woman who built Hallwyl palace wanted to catalogue everything already from the beginning. She must have known that the exploitation of the workers that took place in Ljusne with surroundings was completely unsustainable. So better make a museum while she could.

Gabriel: You could organise bus tours from Ljusne to Hallwyl Palace.

Ebba: The union club at the plywood factory used to do that. They stood there and cried when they saw all the gold taps.

Tova: Will we stand crying somewhere, and, if so, where?